BBC News, 24 June 2021

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESEgypt is trying to strengthen its diplomatic and military clout in Africa amid an escalating dispute with Ethiopia over the building of a huge dam on a tributary of the River Nile, writes Egypt analyst Magdi Abdelhadi.

The Egyptian Geographic Society, established in 1875, houses some valuable manuscripts that reflect Egypt’s long-standing interest in sub-Saharan Africa.

Among them is a historic map that shows the southern borders of Egypt at Lake Victoria in East Africa.

The society was established at the height of Egypt’s short-lived imperial ambition, which had brought Sudan under Egyptian control and sought to conquer Ethiopia in a disastrous military expedition from 1874 to 1876. It ended in a humiliating defeat.

Some 70 years later, Egypt atoned for its imperial misadventures when it became the standard bearer of anti-colonial struggles in Africa and beyond.

But as it got sucked into the Arab-Israeli wars, its engagement with sub-Saharan Africa dwindled.

The past few years, however, has seen a dramatic re-engagement, in particular with the Nile Basin countries.

Egypt has signed a string of military and economic agreements with Uganda, Kenya, Burundi, Rwanda and Djibouti in recent months.

Cairo already has substantial integration agreements with Sudan, where it recently conducted joint military exercises involving warplanes and special forces.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESEgypt has linked its power grid to Sudan’s and plans are under way to connect the railway networks too, with a grand vision to run a train service from Alexandria to Cape Town.

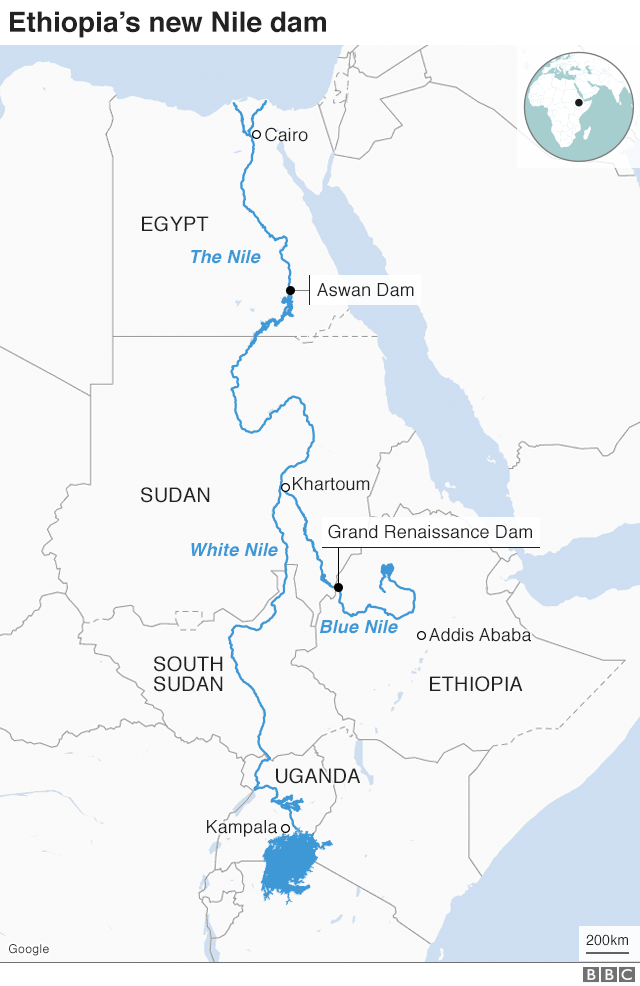

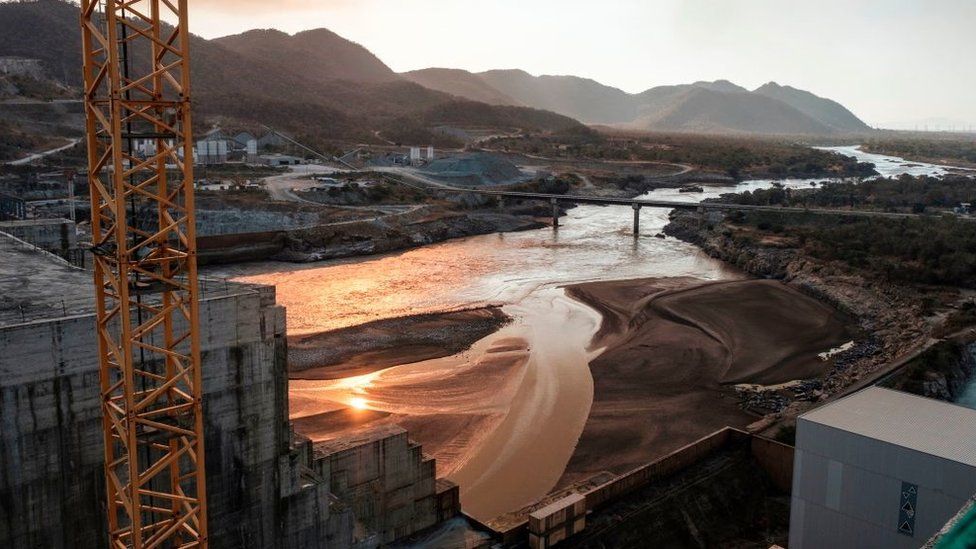

The keyword behind this foreign policy change is the controversial dam Ethiopia is building on the Blue Nile, known as the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (Gerd).

“Egypt has long relied on diplomacy to solve its differences with Ethiopia over the Gerd. But the track of negotiations seems to have been exhausted, or nearly so,” says Nael Shama, an expert on Egyptian foreign policy.

Fears of drought

Tanzania is another example, where Egypt is investing heavily in the massive Julius Nyerere hydroelectric dam on the Rufiji River. Cairo clearly wants to highlight the project as an example of its willingness to help development in the Nile Basin countries.

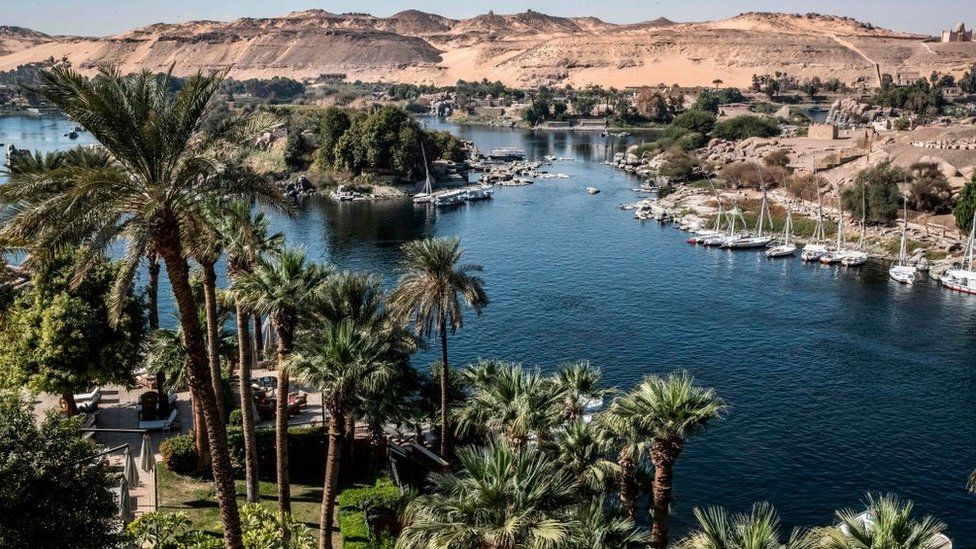

And this is precisely the kind of message Egypt – which has no other major sources of water for drinking and agriculture than the Nile – has been trying to relay to global opinion.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESIt is not opposed to the Ethiopian dam per se, but it is extremely wary of its likely impact on the flow of the Nile waters if Ethiopia refuses to sign up to a legally binding agreement on how to manage its operations.

It is feared the dam could decimate Egyptian agriculture and lay waste to large swathes of its arable land, triggering massive drought and unemployment. Ethiopia, on the other hand, sees the Gerd as vital to its development needs, and the supply of electricity to its population.

Trade links, not military muscle

Egypt’s change of direction and focus of foreign policy towards sub-Saharan Africa is therefore long overdue, but, some Egyptians say, it is too little too late.

“Clout in modern politics is not just guns and cannons,” argues Walaa Bakry, an academic at the UK’s University of Westminster and a business consultant.

“Security agreements with some of the Nile Basin countries such as Burundi, Rwanda or Uganda is a good thing, but will not give Egypt the clout it wants,” he writes.

Strong trade links can achieve far more than military muscle, he argues, pointing to the minuscule trade Egypt has with all nine Nile Basin countries.

“No-one is saying that Egypt should buy anything it doesn’t need from these countries. But for example, the Nile Basin countries produce huge amounts of high-quality coffee – Egypt imports coffee for well over $95.5m annually, 95% of that is from outside Africa.”

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGESMeanwhile, the mood in Egypt has grown increasingly bellicose. The Egyptian regime, in fact the president himself, is under enormous pressure to get tough with Ethiopia.

Even supporters of Abdel Fattah al-Sisi have started to mutter the unthinkable – that failure to protect Egypt’s water rights would mean he would no longer have the right to rule.

Egypt apparently hopes that building a ring of allies around Ethiopia would pay off in some form if a showdown with Ethiopia becomes inevitable.

Egypt and Sudan have taken the dispute over the dam to the UN Security Council, as they consider it could potentially threaten peace and stability in the region.

The issue has been before the Security Council before, which referred it to the African Union, which failed to resolve it.

Both Cairo and Khartoum blame Ethiopia for that, while Addis Ababa accuses Egypt of using the negotiations as a ploy to re-assert its effective monopoly of the Nile waters – a reference to Egypt’s lions’ share of the water.

Egypt’s agreements of military cooperation with Uganda, Kenya and Burundi appear to reinforce that message, although it is hard to imagine these countries agreeing to be sucked into a regional war where their key national interests are not at stake.

If all diplomacy fails, there is little doubt that public opinion in Egypt will back military action if need be.

Less so in Sudan, where there is a certain degree of ambivalence, not least because, unlike Egypt, Sudan stands to benefit from the dam, which will reduce destructive flooding and give it cheap electricity.

But there is broad consensus among observers that, although Egypt and Sudan may have the political will and the military hardware and skill, a strike of some kind targeting the ongoing construction of the dam to set it back by a few years will not solve the problem.

Instead, it will increase mistrust and re-fuel the discourse of ancient grievances, nationalist pride and revenge.