09 August 2021

By

A tally of the numbers of migrants who die or go missing during their journeys is impossible to establish definitively, since so many go without telling people, and travel via illegal means. Deaths at sea are even harder to trace, because many of the bodies are never recovered. The Atlantic Crossing from West Africa towards the Canaries is one of the worst routes for this.

Officially, the IOM Missing Migrants project counted 250 people who died or disappeared on the Atlantic Route between West Africa and Spain’s Canary Islands between January and June 2021.

Unofficially, that figure could be much higher, admits the UN migration agency IOM. As Julia Black from the Missing Migrants project states in one of their recent podcasts, more than two thirds of those who go missing at sea are never recovered.

In fact, the Spanish NGO Caminando Fronteras (Walking borders) recently estimated that as many as 2087 people had lost their lives trying to reach Spain in 2021, more than 1,900 of them on the route to the Canaries, across the vast Atlantic Ocean.

Lost without a trace

Many more migrants are never even registered as having left because they sometimes don’t tell their families they are leaving and travel via smugglers and without papers, making it difficult for any official tally to even begin.

That was the experience of Mbaye Babacar Diouf, who left Senegal in 2003 and spoke to InfoMigrants for our forthcoming podcast project Tales from the Border which will be online in October. It was several months after he finally arrived on the Canary Islands before he was able to contact his mother and tell her he was safe.

“It was only nine months later that I finally told her I was in Spain as I wasn’t able to talk to her for that long. I was told by a friend of mine that she thought I was dead, that I had died at sea all that time,” Mbaye explained in an interview for the podcast.

‘I made the decision to go all alone’

Luckily for Mbaye, he survived to tell the tale and almost 20 years later is now flourishing in the Basque country where he lives and works as a nurse. But his journey at just 15 years old mimics many others who are attempting to reach Europe today.

“I made the decision to go all alone. If I had told my Mum what I was doing, she wouldn’t have let me go. So I had to lie to her. I told her, I am going off to play football with my friends for a few days. She asked how long? I said ‘oh, three or four days, something like that.'”

The impact on the families who lose loves ones is even greater. The Missing Migrants project estimates that for every death or person missing, at least 15-20 more people are impacted. For women, the widows, mothers, or sisters of these migrants, the impact can have a double sting.

Women are often impacted more strongly by a disappearance

Whichever route a migrant travels, when they go missing, says Tekalign Mengiste, who led the research for the IOM into the stories of families in Ethiopia who have lost loved ones on a migration route, women like men experience the grief of losing someone, the unresolved grief of not knowing what happened to that person, and women in particular often find themselves disinherited if they can’t prove the death of that person.

Women whose husbands or brothers go missing are often then dependent on other family members for their survival but conversely can still often carry the burden of clearing the debts of the migrated person, which are not cancelled when the person doesn’t reach their destination.

‘My hopes and dreams left with my daughter’

One Ethiopian woman told Mengiste and his team that her “hopes and dreams” had left with her daughter. She testified that she sometimes “talked to myself like a madwoman,” and that she had “long waited to see her daughter’s face, but my wishes remain a daydream.”

The woman, who wished to remain anonymous, said that even now, “every time someone knocks at the door,” she “runs, hoping it is my daughter who has come back.” The woman said that she was sure her daughter wasn’t dead because “I see her in my dreams.” She concluded that her “heart tells me she is alive.”

Another man who lost his son said his wife had suffered a heart attack when she was told of his disappearance. The man himself said he was also no longer able to work on the farm because all he could see was “the face of my boy again and again.” The man said he “couldn’t sleep at night because his voice and image come to my mind, every minute.”

Dead bodies in the Caribbean

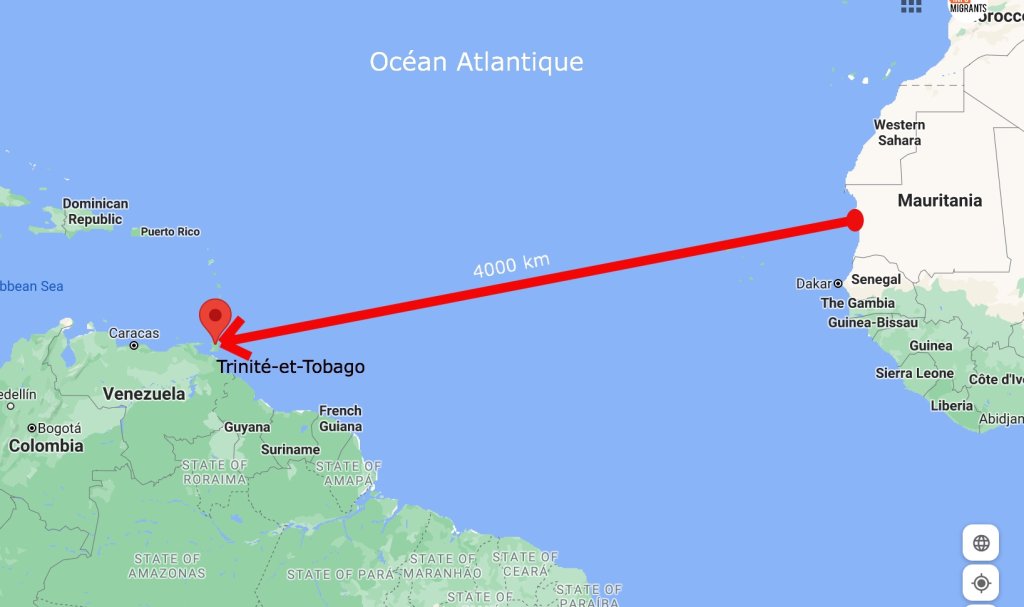

Some of the missing migrants who attempted the Atlantic route have turned up right across the other side of the ocean in the Caribbean. William Nurse, an assistant commissioner with the Trinidad and Tobago police, recently told reporter Sam Jones for the Guardian newspaper of his memories of being called to the discovery of a boat full of decomposing bodies in May this year.

Nurse remembers, “I’d never seen a boat come in with so many bodies. I’d never seen anything like it. Most of the bodies were concentrated in the middle of the boat. There were two bodies to the rear of the boat and there were a few towards the bow. I think one of those ones towards the bow was the last to die because there was still hair on the head.”

In fact, on board the pirogue (wooden boat) which was registered in Mauritania, there were 15 bodies and some skeletal remains. The police said that the outboard engine on board was “far too small to properly power the 42-foot long boat.” According to the Guardian, police also say they “found a total of 1000 Swiss francs, €50 and a number of mobile phones.”

Skeletal remains

Postmortem examinations confirmed that the bodies were those of African men. Fingerprints have been taken from three of the least decomposed bodies and Nurse and his team are hoping that will help identify at least those people, but for the rest, they may never be named and are at the moment lying in a morgue in Port of Spain.

Six weeks after the Tobago discovery, another boat, also carrying 15 bodies washed up on the shores of the Turks and Caicos, also in the Caribbean Sea.

Mbaye recalls that on his journey back in 2003, they also passed a boat full of dead bodies during their ten-day crossing to the Canaries. “They were people who had set off the week before us and they died during the journey to Tenerife. When we saw these people dead in their boat, we had a lot of different things running through our head. We could have been those dead people, we could have been in that earlier boat. Will this happen to us, we thought, since we also didn’t know where we were going. We nearly lost it,” he remembers. Luckily, those on Mbaye’s boat didn’t lose it and two days later, they made landfall on Tenerife.

Julia Black from the Missing Migrants, speaking in a podcast, said that when we talk about the number of people who died or go missing, the people are just a statistic. That is why the team at Missing Migrants decided to start gathering the stories of families who are left behind, to try and document just some of the stories of people who never made it.

About ‘1 in 4 or 5 never make it to their destination’

Again, the numbers of those who went missing, be it on land or sea, are impossible to estimate accurately, but Mengitse says that from the interviews he conducted in Ethiopia, one in four or five migrants who leave their home area don’t make it to their destination.

Many migrants who leave know the risks that face them but the desire to make a better life and provide for their families push them forwards in spite of that. Babacar Ndiaye, a former fisherman from Senegal told the Guardian that he was unable to earn enough back home, “so I decided to leave my wife and two daughters behind and come to Spain. It was pure chance that we made it,” he says.

Ndiaye is now volunteering at the local church, helping make sandwiches for locals and migrants who need help from the soup kitchen to get by. But Ndiaye is desperate to receive his papers so he can start work and send money home. And it is that and the desperate situations caused by war and poverty that many leave behind, which will continue to motivate people to attempt to cross the sea or land borders in the hope of arriving in Europe.

Source: Info Immigrants

These migrants made it to the Canary Islands from Morocco but many more die at sea. Perhaps nearly 2,000 in 2021 alone | Photo: Javier Bauluz / AP

These migrants made it to the Canary Islands from Morocco but many more die at sea. Perhaps nearly 2,000 in 2021 alone | Photo: Javier Bauluz / AP